Eglantyne’s Achievements

(Click on Image to Enlarge)

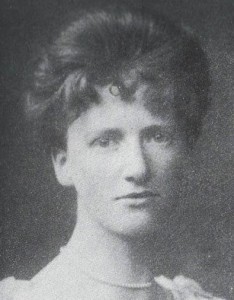

Raised as an Anglican Eglantyne Jebb was born at a time when women were of scant consequence in church hierarchies. None the less she caused Randal Davidson, then Archbishop of Canterbury, to change his mind. She also secured an audience with Pope Benedict XV who issued an encyclical naming for the first time a non-Catholic organisation. Much of her successful relief work was undertaken with the Society of Friends. Later she preached from Calvin’s pulpit in Geneva and at an ecumenical service held at St. Martin’s in the Fields.

Raised as an Anglican Eglantyne Jebb was born at a time when women were of scant consequence in church hierarchies. None the less she caused Randal Davidson, then Archbishop of Canterbury, to change his mind. She also secured an audience with Pope Benedict XV who issued an encyclical naming for the first time a non-Catholic organisation. Much of her successful relief work was undertaken with the Society of Friends. Later she preached from Calvin’s pulpit in Geneva and at an ecumenical service held at St. Martin’s in the Fields.

She was also born at a time when women were of scant consequence in political life. Nevertheless she confronted David Lloyd George’s post First World War British Government and arguably won. She became an assessor at the League of Nations, was acclaimed by the Budapest Parliament and received by the King of Bulgaria She gained the respect of ministers of state at home and abroad.

Her great achievements are the relief of children’s desperate needs in the aftermath of the First World War. In the post war years Eglantyne was immensely active in trying to provide relief wherever it was needed, From the creation in January 1919 of the Fight the Famine Council there emerged a Children’s Committee and soon after the organisation we now know as Save the Children. helping to put people into a position to help themselves. At the same time she was an assessor for the League of Nations, successfully drafting the Declaration of Geneva on the Rights of the Child which was signed by many international dignitaries and statesmen.

The Formative Years

It is in Eglantyne’s formative years at home and abroad that she gained skill, knowledge and understanding to meet the challenge posed by the immediate aftermath of the First World War. Eglantyne’s father had set up in Ellesmere a debating society. It was not merely for the great and the pompous to hear their own voices. At least one of his house servants took part in a debate. Eglantyne and others learned that informed, public discussion could lead to evidence based conclusions. Eglantyne’s mother established a Home Arts Movement which aimed to spread knowledge and practice of useful skills. Launched in Ellesmere and Rhiwlas the movement spread widely and gained royal notice. One by product of this dissemination of skill and knowledge was that needy people were often put into a position to help themselves.

Supported by her Aunt Bun and, reluctantly, by her father Eglantyne went to Oxford where she studied history. During that time her father died and soon after her brother Gamul. Both are buried at Rhiwlas, a hamlet in Llansilin west of Oswestry. After Oxford Eglantyne trained as a teacher in East London and was appalled by the conditions in Wapping. Having worked as a teacher for one year in Marlborough she became companion to her mother who had removed to Cambridge. There she became secretary to the Cambridge Charities Organisation Society and wrote an extensive report analysing the causes of urban poverty. In it she observes

“We have created the urban poor ourselves and are responsible for them. Year by year lives are wrecked which might have been saved and the responsibilities for the suffering and failure rests with us.”

Travelling abroad with her mother Eglantyne visited Germany, Switzerland, France, Italy and Denmark all the while developing and using her foreign language skills. But of the hotels and their users she commented

“Hotels like this are as workhouses for the poor, they are the last refuge of the incapable and the unemployed.”

Macedonia : 1913

Eglantyne went to Macedonia on behalf of the Macedonian Relief Fund. This area of the Balkans had long been the place of religious, ethnic and linguistic differences leading to conflict. Albanians, Serbs, Ottoman Turks, Muslims, Catholics and Serbian Orthodox were frequently in conflict. Atrocities had been reported and the fund wished to investigate what had happened. Having decided that a woman would be less likely to fall under suspicion Eglantyne was asked to go. She had the advantages of being fluent in several languages, was an experienced traveller, was not afraid to be alone and was known to be astute and adept in difficult situations. Travelling by train to Belgrade she met the British Consul and was provided with a Serbian military officer as escort. She recognised that she needed to give this escort the slip if people were to respond openly to her. Having done so, she was able to establish that atrocities had taken place but on a smaller scale than had been reported. In addition to completing her mission Eglantyne saw at first hand the aftermath of war – the movement of refugees; the steady loss of their possessions as they were sold to buy food; people in fear; people in hunger and the effect on their children.

The War Years and their Aftermath

In 1915 Eglantyne’s sister Dorothy had sought and gained permission to import via Scandinavia foreign newspapers both allied and neutral. Her aim had been

“to supplement the English press by providing information on the points of view of other countries ……. In connection with the war.”

Eglantyne became involved in translation work from 1917 onwards taking responsibility for Swiss, Italian and French newspapers. A digest of translations was published periodically. As with other journals it was subject to censorship. The digest was read in Washington and at home by Smuts, a member of the cabinet, and Lord Lansdowne, a former foreign secretary. The sisters were also aware from their reading of the great and extensive hardships being experienced in enemy countries. Before the war ended there was civil insurrection in Cologne. Eglantyne and Dorothy knew of famine from Finland to Rumania. They were greatly exercised by mortality in women and children. But the situation in Vienna was to cause even more anxiety as yet more information emerged early in 1919.

After the Armistice

To those who knew of the effect of the war on the civilian population of enemy countries the Armistice was a great relief. But the blockade on supplies to enemy countries did not stop with the Armistice. In January 1918, a mere six weeks after the Armistice Dorothy and Eglantyne were part of a Fight the Famine Council. Their aim was to raise an international loan to give relief to the populations of former enemy countries but Blockade and censorship continued. The sisters argued publicly that women and children were the abiding casualties of war and that England remained blockaded against the truth. Their case fell largely on deaf ears. The government did not wish to know until a peace treaty had been signed. Some doubted the truth of what the sisters were saying; others thought that even if it were true it was simply the enemy getting their just deserts.

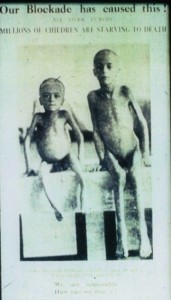

Early in 1919 Dorothy visited Vienna. She reported that the great mass of the population was starving. Other sources confirmed her findings. The Council continued its work as best it could in difficult circumstances. In April it formed a Children’s Committee and Eglantyne was given charge of its work. Increasingly exasperated by the continuing plight throughout much of Europe and government inaction Eglantyne caused uproar by publishing a leaflet without permission. The leaflet was indeed grim.

(Click on Image to Enlarge)

The leaflet was indeed grim. The boy on the left aged eight weighed less than two stones. The boy on the right aged ten weighed little more.

The leaflet was indeed grim. The boy on the left aged eight weighed less than two stones. The boy on the right aged ten weighed little more.

Eglantyne was clear that the difficulties had been the direct result of Blockade policy carried out by the government. She urged everyone to write to the prime minister, David Lloyd George, urging that the Blockade be stopped and allow relief to be given.

The leaflet did more than draw attention to a problem. It confronted government policy and could only be seen as an embarrassment. It also broke the law in so far as it had been published without permission when Censorship was in force.

Response was swift. In May Eglantyne was charged with publishing a leaflet without permission, convicted and fined.

Two days later Eglantyne spoke to a packed Royal Albert Hall. Generous donations were made helping with immediate relief but Eglantyne knew from her experience in Shropshire, Cambridge and Macedonia that people would need to be put into position to help themselves.

After the Peace Treaty had been signed the government became a major donor. In 1919 there were church collections throughout the world. Funds raised were now used as far as possible to establish enduring projects. Eglantyne initiated relief practices that are now commonplace in international relief work. But Eglantyne’s work for the League of Nations is perhaps her greatest achievement.

The Declaration of Geneva

(Click on Image to Enlarge)

Although there had been general agreement on the need to have a formal statement concerning the protection and development of children concise, formal expression of that ambition was Eglantyne’s achievement. The Declaration was adopted by the League of Nations in 1924 and later by many member states. It was also adopted throughout the British Empire.

Although there had been general agreement on the need to have a formal statement concerning the protection and development of children concise, formal expression of that ambition was Eglantyne’s achievement. The Declaration was adopted by the League of Nations in 1924 and later by many member states. It was also adopted throughout the British Empire.

Asserting generally that children are to be provided with the means of normal development it continues by asserting how children in adverse circumstances must be provided for. It further asserts that children must be the first to receive relief.

The mirror of these rights of the child, although unsaid, has to be adult and state responsibility. Articles four and five again presume adult and state responsibility for placing children in a position to earn a living while being protected from exploitation.

Article five asserts that children must be brought up to use their talents in the service of their fellow men, truly a demanding parental and state responsibility.

The Declaration of Geneva has been influential ever since its adoption. It has echoed down the years the principles being adopted by the United Nations and many of its member states.

Some Further Reading

Rebel Daughter of a Country House: Francesca Wilson: 1967

Far Above Rubies : see chapter 3 : Richard Symonds : 1993

The Woman Who Saved the Children : Clare Mulley: 2009

©Charles Stiles 2012

This article is copyrighted, please contact the group before using any information or pictures, held in this article.