“Tommy, thou has brought me to this shameful end, but I freely forgive you.”

These dramatic words were almost the last spoken by Thomas Phipps to his twenty year old son. Moments later they climbed onto the scaffold to be dispatched, hand in hand, into eternity.

The circumstances that brought the Phipps, father and son, to this terrible end are complicated. Not only because of the actual events but, viewed through the eyes of a twenty first century reader, this simple case appears to be one which could have been easily resolved by a fine or a short prison sentence. Throughout their trial the prosecution case was vigorously disputed by the two accused but to no avail. They were convicted of forgery and, in 1789, death was the penalty they had to pay.

Thomas Phipps was an Oswestry man, the scion of several generations of Phipps. He was baptised at St Oswald’s in 1743, His father, Vincent, was a respectable grocer in Cross Street and later Bailey Street, who in time became mayor of the town. Vincent was married to Jayne on the 29th June 1733 who gave birth to three children, Jayne, Richard and William before dying three weeks after William was born. Nine years later Vincent married again, to Sinah Lloyd who is thought to have come from Llansilin. She and Vincent went on to have Thomas, Robert and Eleanor.

Vincent was relatively wealthy and able to give his children a good education and eventually Thomas took his articles to become a lawyer and set up in practise in Oswestry. It would seem that he flourished, his name is prominent on many wills, particularly in the Llansilin area. It appears that he also had business interests in London.

On the 29th of January 1768 Thomas married Emma Davies from Llwynymapsis and she bore Thomas four children of whom only two, Emma and Thomas junior, known as Tommy, survived into adulthood.

So here we have Thomas Phipps, solicitor, businessman, described as a landed gentleman, who had a successful practise in Oswestry and lived and farmed a couple of miles outside the town at Llwynymapsis, a small hamlet close to present day Morda. He was described as being worth about £500 a year from land and business besides his income as a lawyer.

In 1786, aged 17, Tommy took articles of clerkship with his father and started his legal training.

Sometime in 1787 or 1788 Thomas senior leased two parcels of land to William Howell, a local butcher, who subsequently sub-let them to Richard Coleman, at a fixed rent of £20.00 per annum, on the understanding that Coleman would graze one parcel of land and cut and stack the hay on the other, on behalf of the landowner. Thomas Phipps senior agreed to this arrangement, although there seems to be nothing in writing to substantiate it.

Richard Coleman was the husband of the landlady of The White Horse Tavern in Cross Street. Previously he’d been an Excise officer but when he married Margaret Edwards, who was the licensee of the pub, the law required that he give up his profession. Witnesses tell of an angry man who liked a drink.

In 1788 Thomas Phipps senior went away to London on business for some weeks but on his return, found that the hay on both parcels of land had been cut and instead of being stacked, had been taken away by Richard Coleman.

He was furious and by Christmas 1788, a writ had been served on Coleman at the cost of £2. 3s. demanding £32 for the hay which Richard Coleman had taken. It seems that this enormous amount had been demanded by Tommy and that Thomas senior was unaware of it. Later, when he learned of it, Thomas senior said that £20 would suffice. Coleman, having taken instruction from his lawyer, refused to pay. The implication in the later trial was that Coleman had permission to take the hay.

The argument rumbled on with hard words between the two parties and no payment was forthcoming.

Then, months later, frustrated by the defiance of Richard Coleman, the Phipps, father and son, declared publically that Coleman had on the 7th March 1789, signed a ‘non pros’ for satisfaction of a trespass by him committed in carrying off the hay. The note signed was for £20.00 and witnessed by Thomas Phipps, Thomas Phipps junior and William Thomas, their sixteen year old clerk. It read as follows:

I Richard Coleman of Oswestry in the County of Salop, yeoman, do hereby promise to pay unto Mr Thomas Phipps of Llwyn-y-Mapsis in the said county or his order the sum of twenty

pounds with the lawful interest thereof upon demand for value received as Witness my Hand this seventh day of March one thousand seven hundred and eighty nine.

£20 Richard Coleman

Witness: Thos Phipps junr

William Thomas junr

A non pros is a shortened legal term meaning that in return for a sum of money no prosecution will follow.

Richard Coleman vehemently denied that he’d signed the note and insisted that it was a forgery and instructed his lawyer, Robert Lloyd, to defend him.

A warrant was made for the arrest of Phipps, father and son and William Thomas. When the constable, John Phillips, arrived at Llwynymapsis he found Thomas and Tommy in the cellar, armed with a brace of loaded pistols. Thomas was taken immediately but Tommy escaped. Handbills were published with his name and likeness and he was recognised by a gentleman from Oswestry who was on holiday in Towyn. He was captured ten days later by one Richard Evans, sixty miles away in Cardiganshire.

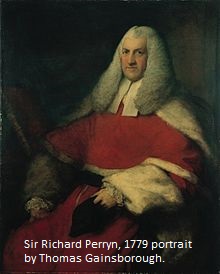

The case came to court in Shrewsbury on Tuesday 11th August 1789 in front of the Honorable Sir Richard Perryn, where Thomas Phipps senior, gentleman, Thomas Phipps junior, yeoman, and William Thomas, yeoman, were accused of forgery.

where Thomas Phipps senior, gentleman, Thomas Phipps junior, yeoman, and William Thomas, yeoman, were accused of forgery.

At the trial the prosecution brought forward witnesses who knew Coleman from his days as an Excise officer; they swore that the handwriting on the note wasn’t his. Journals were produced in which Richard Coleman had written up case notes from his days in that service to show that his signature on those, and on the promissory note, were markedly different.

Coleman’s lawyer, Walter Williams, who had been approached when Coleman had first been accused of taking the hay, swore that Coleman had said nothing about a promissory note. And another witness, William Howell, swore that in conversation with Thomas Phipps senior, Phipps had said he would have dropped the action entirely if Coleman hadn’t assaulted his son, Tommy.

The most damning evidence came from the sixteen year old clerk, William Thomas. In court he repeated the confession he’d made a few weeks earlier to Lewis Jones, Mayor of

Oswestry, that he had not seen Richard Coleman sign the promissory note. Tommy had brought the note to him at the Drill public house and made him sign as a witness. Then, when he and Tommy went to Shrewsbury to swear an oath that this was a true note, William had refused, adding that he would not throw away his soul to the devil. ‘Slip the book aside,’ Tommy told him, ‘and then swear.’ He wouldn’t.

For the defence, witnesses stated that at the beginning of July, Richard Coleman and young Tommy had an argument in the street in Oswestry. One witness, Mrs Mary Vernon, said that she heard Tommy say ‘You have done injury to my land and I shall make you pay for it.’ Coleman then abused him and said, ‘If I do pay for it, it shall be by turning up and throwing you the other side of it.’

When asked about the characters of the Phipps, whom she had known all her life, she could say no ill of them. But she did believe that Coleman ‘…had been in liquor’ at the time of the argument.

Margaret Jones, who had been a servant in Llwynmapsis, swore that she heard Coleman promise to stack the hay. She admitted under cross examination that she had only mentioned it to Edwards, the defence lawyer, a week ago. He arranged for her to meet Mr and Mrs Phipps, at the Talbot, where they talked for some time. She further said when interrogated, that her father was a tenant of Mr Phipps.

Mr Charles Jones, a skinner, swore that he’d been at Phipps’s house when Coleman had promised to graze one parcel of land and mow and stack the other. On interrogation he admitted that he too was a tenant of Mr Phipps and that he couldn’t exactly remember where he’d been when this conversation had taken place nor when it had occurred.

Mrs Margaret Kyffin stated that her late husband had been a tenant of Thomas Phipps and had always found him an upright and honest man. On being asked if Coleman was a drunken man she replied, ‘He drinks sometimes.’

The judge interrupted then, surprising everyone by saying that Richard Coleman’s character must not be part of the defence.

Several other witnesses, John Bill, Richard Griffiths, Mr Windsor, Mr Pugh and Mr Hamilton came forward to testify to Thomas Phipps’s honesty and fair dealing.

In his summing up to the jury, the judge made much of Thomas Phipps’s previous good character, however, he stated that the actual evidence brought before the court was difficult to ignore. He left the decision up to the jury’s individual consciences.

The jury deliberated for twenty minutes and then returned a verdict of guilty. They recommended mercy for the younger Phipps on which the judge expostulated that he considered Tommy to be more guilty than his father.

They were sentenced to death by hanging.

William Thomas, due to his youth, was considered a mere tool of the Phipps and had willingly confessed. He was found not guilty and acquitted.

Thomas and Tommy awaited execution at Shrewsbury jail for a month after their sentence. There is no indication that an appeal was mounted, but friends loyally stayed with them. They still insisted their innocence until 5th September 1789, the morning of their execution, when young Phipps made a confession. “It was I alone who committed the forgery: my father is entirely innocent, and was ignorant of the note being forged when he published it.”

The confession came too late to save either of them and, on a remarkably wet day, they made their way to the hanging tree, in a coach, accompanied by a clergyman and one of their friends.

“Tommy,” his father said, “you have brought me to this shameful end, but I freely forgive you.”

Because of the terrible weather they made their devotions in the coach and when the final moment arrived, Mr Phipps said to his son, “You have brought me hither; do you lead the way.” The youth promptly did and in a most composed manner led the way to the noose, followed by his father.

Despite the rain, there was a vast concourse of spectators who’d come to see the execution and witnessed the father and son embrace each other. In a few moments the trap fell and hand in hand they were launched into eternity.

In a letter published on 21 July 1915 in the Borders and County Advertizer, a woman identified only as J.M. wrote that, as a little girl, she had been told that the Phipps’s bodies had been secretly brought back home on the night they died, in the clothes they wore at

execution. She was taken to see the Phipps’s grave in Morton churchyard where she said it was in the far right hand corner, bearing no name but the initials J.P.

Another account, however, says that in 1825 the skeleton of the elder Phipps was kept by a Doctor M.E. Dovaston in his surgery in Llanymynech.

Strangely, the disgrace of execution had little effect on the remaining family. Thomas’s daughter, Emma, married Samuel Jones and after the execution they took up residence at Llwynymapsis. Their daughter, Jane Emma Jones married George Dorsett Owen, mayor of Oswestry in 1838 and their son was Charles Whitley Owen, the local brewer.

The details of any case from so long ago appear, necessarily, confused, as the practises of eighteenth century law look somewhat strange to modern eyes. The Phipps’ were, by at least one telling, accounted as local heroes, for whom succour was provided when the younger of them was on the run. Coleman, while quite possibly wronged and his name traduced, seems to have left Oswestry almost immediately after the trial. He does not come across as a likeable figure and perhaps that was the case then.

It is this sort of confusion which is both the delight and despair of the local historian. Whatever the facts may truly be, the story of Phipps v Coleman is one of drama and intrigue and I am glad to have this opportunity to bring it to your attention.

Sources:

MOML Making of modern Law Trials 1600-1926 Anonymous

Oswestry Borderland Heritage Llwynymapsis Colliery

The Newgate Calendar

Borders and County Advertizer 21. 4.1915 Bygones

Borders and County Advertizer 21. 7. 1915 Letter J.M.

© Katherine Rosenberg